Short and simple: stretching improves flexibility. And flexibility enhances performance, reduces injury risk, promotes healing and it feels good to stretch! But did you know there are different ways to stretch to meet specific goals? I’ll explain nine popular types of stretching and offer advice on getting the most out of your stretch.

The Benefits of Stretching

Any athlete knows that stretching before and after exercise is imperative. And as we get older, many of us find that stretching in the morning is a great way to get limbered up for the day. But there’s more to stretching than just bending over to touch your toes. The American College of Sports Medicine states that everyone should add flexibility training to a regular exercise routine to improve and maintain physical health. Stretching can help to:

- Improve flexibility and joint range of motion

- Relieve pain

- Enhance sports performance

- Prevent injury

- Heal from certain injuries

Knowing the differences among each of the following stretching techniques will help you understand which work best in your daily wellness, exercise, or rehabilitation routine.

Static Stretching

Static stretching is the most common. Unlike dynamic stretching, it does not involve motion. With this type of stretch, you slowly extend your muscle to its maximum comfortable point and hold for 10-30 seconds. Then slowly relax and repeat. This process allows the muscle and connective tissue to lengthen progressively. Static stretching is a gentle way to increase flexibility and should not be painful.

Extending a leg and reaching to touch your toes is a familiar example of static stretching. Other examples are the quad stretch, hamstring stretch, butterfly, figure-four, calf stretch, and lateral flexion stretches.

Static stretching is a great way to start your day or to cool down after exercise. But it may not be the best technique for athletes to improve their performance. Overstretching before a workout can take away some of the muscle tension needed to provide that explosive power. Before a workout, dynamic stretching may be a better way to go. The two types of static stretching are active and passive.

Active Stretching

Also called static-active stretching, this method involves assuming a position and holding it there for a determined amount of time. There is no outside assistance offering resistance, only the strength of your own body.

The relaxed muscle that you are stretching is called the antagonist. The muscle that contracts to initiate the stretch is called the agonist. For example, in a basic hamstring stretch, the relaxed hamstring is the antagonist muscle. The flexed quadriceps and hip flexors would be the agonistic muscles. This give-and-take relationship is called reciprocal inhibition.

Yoga is the most notable form of active stretching. Think of the Warrior, Bird Dog, or Bridge poses. These kinds of stretches can be the hardest to maintain, especially when you’re new to stretching. You should usually hold active stretches between 10-15 seconds.

Passive Stretching

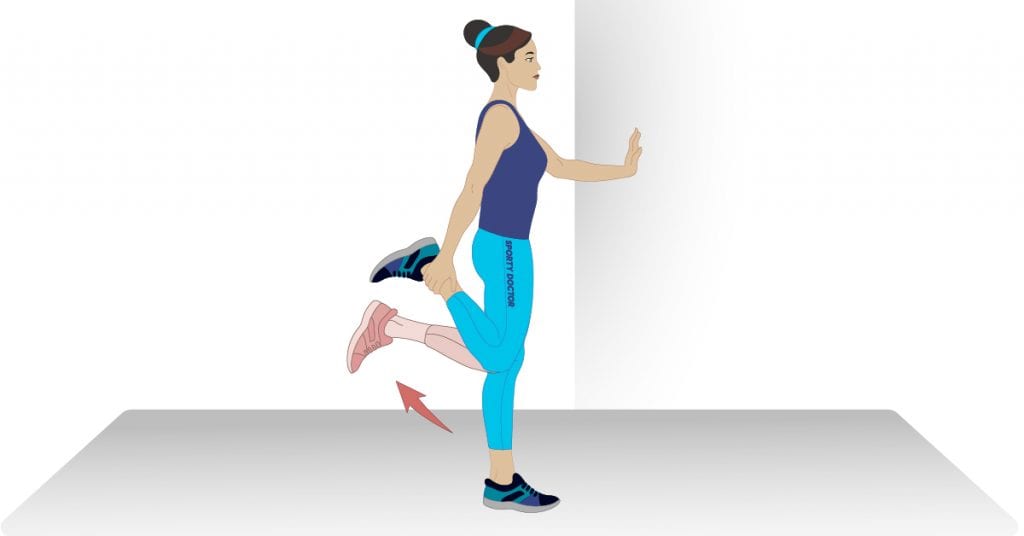

Insert Image: Standing Quad Stretch from

Like static stretching, passive or “relaxed stretching” involves reaching and holding an intended position. The significant difference is that passive-static stretching is done in a relaxed state with the help of external force. It could be your own body, a partner, gravity, a strap, or a piece of equipment.

As opposed to active stretching, placing your leg on a table in a raised position would be a passive stretch. Doing the splits is also passive stretching since you’re using the floor to hold the stretch. The standing quad stretch is another example.

Passive stretching can enhance balance as well as flexibility. It is often associated with physical therapy. It’s best for muscles that are healing from an injury. Great for cooldown, it can also relieve muscle spasms and help with soreness after a workout.

Isometric Stretching

Isometric stretching is a type of static stretching. The muscles are contracted for an extended period while pushing against some form of resistance. Many find it more effective than active or passive stretching alone and a helpful way to build muscle strength. Athletes can gain speed and explosive power when engaging the resistance of muscle groups.

For isometric stretching, you can use your own body, have a partner apply resistance, or use an external source’s resistance, like a wall, floor, or gym apparatus. One of the most common examples is pushing against a wall to perform a calf stretch.

Here’s how you perform an isometric stretch:

- Assume a passive stretching position.

- Then, contract your muscles while pushing against an external force for 7-15 seconds.

- Relax the muscle for at least 20 seconds before repeating.

A session of isometric stretching can be demanding on the stretched muscles. You should not train any muscle group more than once a day with this type. Some examples of isometric stretches are: plank, squats, wall sits, calf raises (holding), lateral raises, and lunges.

Dynamic Stretching

Dynamic stretching requires continuous movement and momentum. You gradually increase your reach by moving in and out of a stretch. Unlike ballistic stretching, this is a gentle approach to the stretch. Rather than bouncing or jerking, dynamic stretching involves a slow, controlled swing.

Dynamic stretching is a useful way to warm up the muscles for aerobic exercise. Rather than holding a stretch for 30+ seconds, you only hold the stretch for 2-3 seconds. This process allows the muscle fiber to increase in length without losing any of that stored up tension. You should usually perform these stretches 10-12 times.

Dynamic stretching is often used to improve flexibility for a specific sport or activity, like ballet, karate, or sprinting. Often athletes will mimic an action done in the sport. For example, a football kicker stretching his hamstring by swinging his leg in an upward kick. He gradually increases the height with each pass.

Other examples of dynamic stretches are high knees, shoulder rotation, butt kicks, leg swings, high kicks, any movement that mimics the activity you are doing.

Ballistic Stretching

Ballistic stretching uses the momentum of your body to force a stretch out of your muscles. Think quick, bouncing movements. With this type of stretching, you reach the end of your range of motion (ROM), then force the muscle a little further.

Quick, jerky movements inhibit the muscles’ stretch reflex, allowing them to increase ROM. This type of “bounce stretching” is often used as a warm-up modality. An example of a ballistic stretch would be bouncing down repeatedly to touch your toes.

Ballistic stretching is not recommended for everyone because it puts unnecessary stress on the muscles and joints. However, it can be beneficial for sports and activities that require quick motions, like basketball, martial arts, or ballet. To reduce the risk of injury, you should precede ballistic stretching with static stretching to loosen up the muscles.

Most static stretches can be converted to ballistic stretches by adding a quick, repeated bounce motion. This includes the standing or sitting toe touch, standing lunge, swinging arms, and swinging legs.

PNF Stretching

PNF stands for proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation. It combines passive and isometric stretching to increase static-passive flexibility more quickly than any other type of stretching alone. With a PNF stretch, your muscle starts in the contracted state and moves into a passive stretch. This process helps to “train” your stretch receptors into a new and improved ROM.

PNF stretching was initially developed to aid in the rehabilitation of stroke victims. Today, therapists often use PNF to treat sports injuries. It is done with a partner- like a physical therapist- since they can apply external force and then guide the limb through its ROM.

There are three phases to a PNF stretch:

- The muscle group is passively stretched.

- External resistance is applied to achieve an isometric contraction.

- The resistance is relieved, and the muscle group once again passively stretched, this time at a greater range of motion. This practice is referred to as post-isometric relaxation and is controlled by the Golgi tendon organs within the muscles.

The hold-relax is the most common PNF stretching technique. Other standard PNF techniques are the contract-relax, the hold-relax-swing, the hold-relax-bounce, and rhythmic initiation.

Loaded Progressive Stretching

Loaded progressive stretching is designed to increase ROM with the aid of an external force, or load. This load can be something like a dumbbell or barbell or the weight of your own body. LPS starts with simple static stretching positions. A load is added to push the body further past its comfortable ROM.

You can also do LPS with a partner, similar to PNF. For example, in the seated position with your legs stretched out, you could have someone push on your back. Or you might put a weight on your back to add force. Adding more weight or having your partner push harder during subsequent stretches brings the “progressive” part into play.

LPS can be an excellent way to strengthen muscles, get a deeper stretch, and hold it longer. But you should be warmed up and well-conditioned first. It’s best to start an LPS routine with a low number of reps and lower weight so that your stretches can be more intense and more effective.

Common examples of LPS exercises are Jefferson Curls, Cossack Squats, and Pancakes. Any exercise that involves ROM can also be used, like Squats or Pullovers.

Active Isolated Stretching (AIS)

A type of dynamic stretching, AIS is performed many times repeatedly on an isolated muscle. However, you only hold these stretches for two seconds at a time. The object is to increase resistance incrementally each time. In AIS, you contract the agonist muscle to get a more significant stretch out of the antagonist. For example, contracting your quadriceps when stretching your hamstring.

A quick AI stretch inhibits the stretch reflex from kicking in and allows for greater muscle lengthening. Today AIS methods are used by many trainers and physical therapists because they are a great way to help the body repair itself while also enhancing performance.

An example of an AI stretch would go like this:

- Lie on your back and use your quad to lift your straight leg up.

- Gently pull on the leg to stretch the hamstring muscle for two seconds.

- Release and repeat 7-9 more times.

Using a rope or band to stretch the shoulder, leg, or calf muscles is another popular AIS example. You can adapt many of my plantar fasciitis stretches into AIS.

The Mechanics of Stretching

A stretch happens when a particular muscle is at the end of it’s ROM or elasticity point. At this point, the muscle contracts to protect you from injury. It’s called a stretch reflex. This contraction is the sometimes-unpleasant “stretch” feeling that tells you it’s time to stop.

Types of stretching like LPS and ballistic stretching use force to push past that comfort zone and reach greater ROM. When you stretch, tiny tears in the muscles release endorphins. The endorphins override the pain sensation, giving you that “good stretch” feeling.

Improving Your Stretching Techniques

Now that you know there’s more than just one way to stretch, it’s time to incorporate this knowledge into your daily stretching routine. Here are some tips to help you increase flexibility and get the most out of your stretch:

- Stretch both in the morning and in the evening. Like getting good at any skill, flexibility requires practice to get proficient. The ACSM recommends performing stretching exercises two or more days a week.

- Always stretch both before and after a workout. Your muscles are warm and most pliable after a workout, affording you the best results.

- Dynamic stretching is best before exercise since it loosens up the muscles. Static stretching should be done after exercise when the muscles are already warm to cool down and maintain flexibility.

- Don’t try to overstretch tired muscles. When your muscles are tired, they lose elasticity. So if you push them beyond their limit, you may be taking a step back in flexibility.

- Focus on your breathing. When you stretch, focus on slow and controlled breathing from your belly rather than from your chest to best engage the diaphragm.

- Incorporate stretching into your daily life. You don’t always have to set aside time to get in a good stretch. Find creative ways to stretch while watching tv or at your desk at work.

- Change up your stretches. Our bodies will quickly adapt to certain routines, so change up your stretching techniques and positions every so often to keep your body working.

- Stay hydrated. Our muscles are primarily composed of water. To respond best to flexibility training, they have to stay hydrated, both before and after exercise.

- Indulge in a massage. Massage can help to break up knots in the muscles that restrict flexibility. Try using a foam roller to promote myofascial release before and after exercise.

- Don’t overdo it. Sometimes a good stretch gives you that “hurts so good” type of feeling. And it can be uncomfortable at times. But stretching should never be outright painful.

You might see practitioners claiming that their stretching method is the best. But ultimately, the best will depend on you. Everyone’s body is different. What are your capabilities? What are your goals? Flexibility takes patience. A beginner won’t be doing the splits overnight. But with time and practice, you will notice a difference.